By Chris Holderness

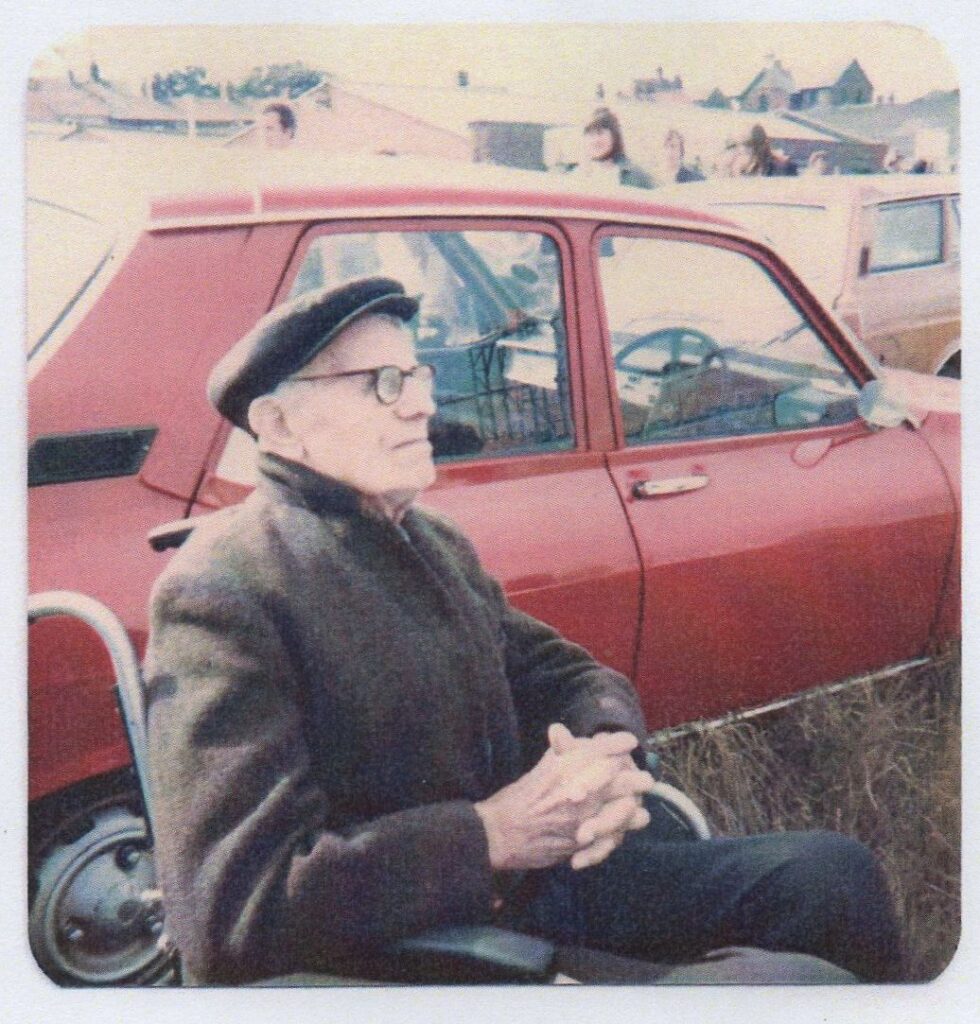

Photo from the family

Photo S Park, Rig-a-Jig-Jig collection

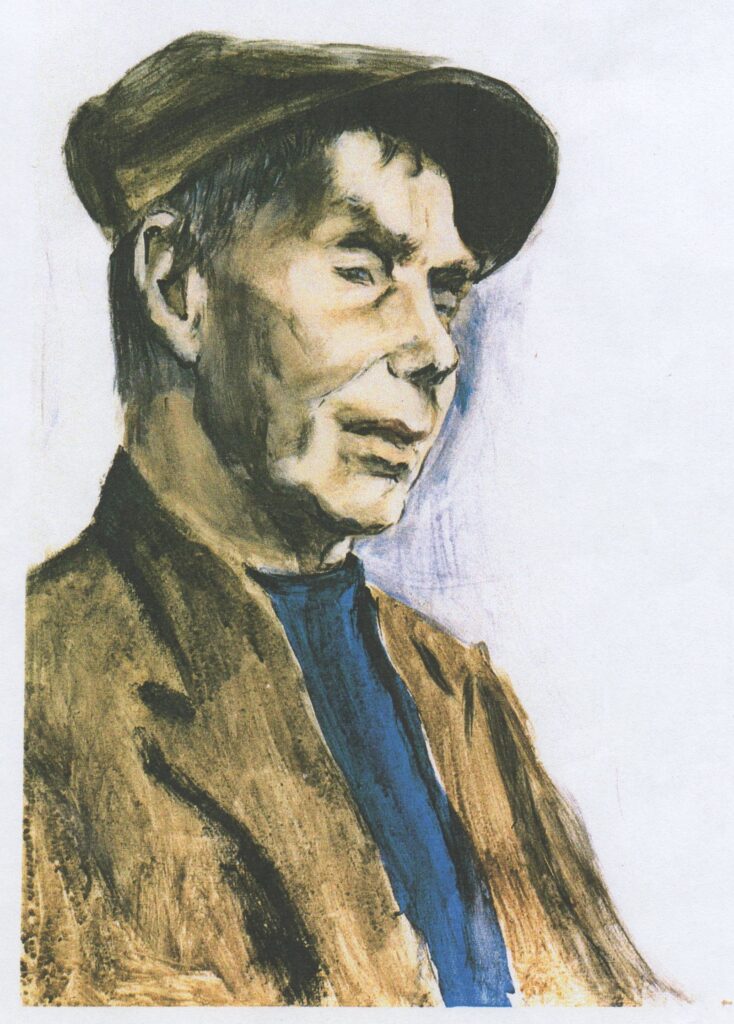

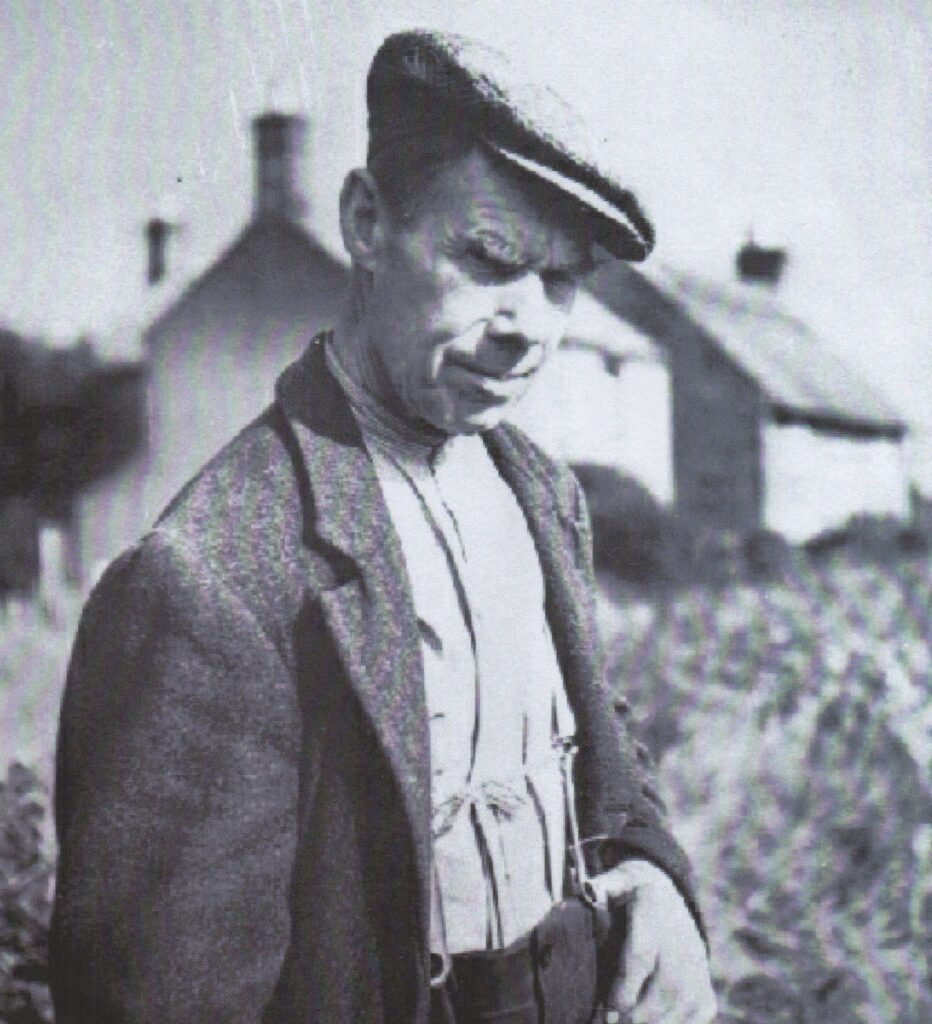

/Harry Cox (1885-1971) was, of course, one of England’s finest traditional singers, with a repertoire of over a hundred songs, as well as playing the fiddle, melodeon and whistle. He was visited at his home in Catfield right up to his death, with countless recordings by both professional and amateur enthusiasts. I don’t propose to give an account of his life, as this has been covered thoroughly elsewhere. For those interested, see the extensive booklet notes to Topic Records’ The Bonny Labouring Boy double CD, by the late Paul Marsh (1) and Chris Heppa’s articles, particularly Harry Cox and his friends: Song Transmission in an East Norfolk Singing Community, c1896-1960 (2). Much else has been written about Harry elsewhere.

Much of Harry’s singing and playing repertoire came from his father Bob, but he learned songs from others in what was a vibrant singing community in the Broads area of Norfolk. Also from elsewhere, as Harry related to Michael Grosvenor Myer and Bob Thompson shortly before his death: “My mother, she used to go to Norwich way over; she was young then; and she had tunes what I learnt. I never see the sheets; my mother learnt them, and I learnt them off her. Down in the Lowlands Low, that’s one she used to sing; no-one never did tell me if that was the tune or not. I wasn’t born when she used to get them sheets.” (3)

Harry continued: “She used to go to Norwich a good bit in them days. Her father, he had no pony and cart and no donkey and cart, but he used to do a bit of digging around about the parish; taters, spuds. And he used to supply them shops in Norwich. She used to go on her old donkey, but that was a darn sight slower than walking. She was only a girl. I suppose she went more then than she ever did after. She never had the damn time to go no more.“

Harry was blessed with a considerable memory which enabled him to remember dozens of songs with ease, even into old age. Likewise tunes, of which he had a large repertoire. (4) “Up to the present I ain’t forgot anything yet. I got a good memory. I don’t forget; I mean I ain’t lost nothing. I have been mixed up sometimes for just one line but you go out of doors that’ll come to you; nobody can tell you. I like old songs. I wouldn’t listen to a song like they make today; never pick up one to learn, ’cause there ain’t one worth it, not to my knowledge. They’re out of my line, and they can do what they like but they can’t sing a song not where there’s sense in it, not like I can.” (5)

Harry would accompany his father to one of the local pubs at quite an early age and would sit on the windowsill, or occasionally hide under the table, and listen to his father’s singing and playing. Local pubs such as Sutton Windmill, Smallburgh Union Tavern and Catfield Crown were regular venues for such music making. Harry first sang in public in the Union Tavern. Although step dancing in the pubs was commonplace indeed, Harry doesn’t seem to have done so; his role was most likely that of musician to accompany the dancing.

credit norfolkpubs.co.uk

“Those old songs, they’re gone now. I was just in the right time to pick up those things. They wouldn’t be picked up now. Barbara Ellen, now I remember it. Some people sing that different to what other people do. You might know a different tune. And there’s some of them put another two verses on the end. I never could. ‘And from her grave grew a rose’. That other one come in Lord Lovely: ‘Where they tied together in a true-lover’s knot, For true loves all to admire’. That’s in another song. They get mixed up; that shouldn’t come in Barbara Ellen. That don’t belong in that. They belong in Lord Lovely (6). My uncle used to sing that. I never did go in for that, I don’t know why. That was out of my line. That was sung by another fellow, and I didn’t want to mix up too many bits.” (7)

“l never did know Captain Ward. My father used to sing it.” Despite Harry’s comment, he was able to recall several lines of the song: “I’ve heard talk about that; I’ve heard: ‘Fight you on, fight you on, said Captain Ward; I value not one pin; For if you are steel without, we are true steel within‘. I never did know it. ‘Fight you on, fight you on, said Captain Ward. Don’t you think much about dying. For the battle will soon be won; keep the cannon balls well a-flying’. Well, that’s how he [his father Bob] used to sing it. That’s how that come along of him.” (8)

Harry may not have learned all of Captain Ward, but he certainly knew a great many songs. Being younger than his fellow local singers, he had ample opportunity to learn from them and built up an extensive repertoire, running to over a hundred songs. He was extensively recorded, and some amateur recordings are still surfacing to this day. He was visited, along with other singers from the area, by the composer E J Moeran from the early 1920s onwards. (9).

The Eastern Daily Press ran an obituary on 8 May 1971: “Father of Norfolk songs dies – Harry Cox, the traditional Norfolk folk singer, has died aged 86. He had been ill for some time. Born at Barton Turf, only a few villages away from Catfield, where he died. Harry Cox was acclaimed as the ‘father of East Anglian folk music’.

“He was honoured last year with the gold badge of the English Folk Song and Dance Society – an award held by only a handful of people. It marked recognition of his exceptional contribution to English folk music. More than 100 local songs would have been lost if he had not remembered them.

“A lifetime on the land bred and nurtured a true traditionalist Norfolk flavour in the singer’s voice, which remained authentic despite his national recognition.

“He was discovered by the Irish folk expert E J Moeran in the 1920s and his songs were published and recorded in the next three decades by enthusiasts like Moeran, Francis Collinson and latterly Peter Kennedy, the folk radio broadcaster. Mr Cox, a widower, leaves a married daughter.”

Credit P Kennedy from East Anglian Folk Singers and Musicians article by Dave Green

Credit P Kennedy from Eastern Daily Press article

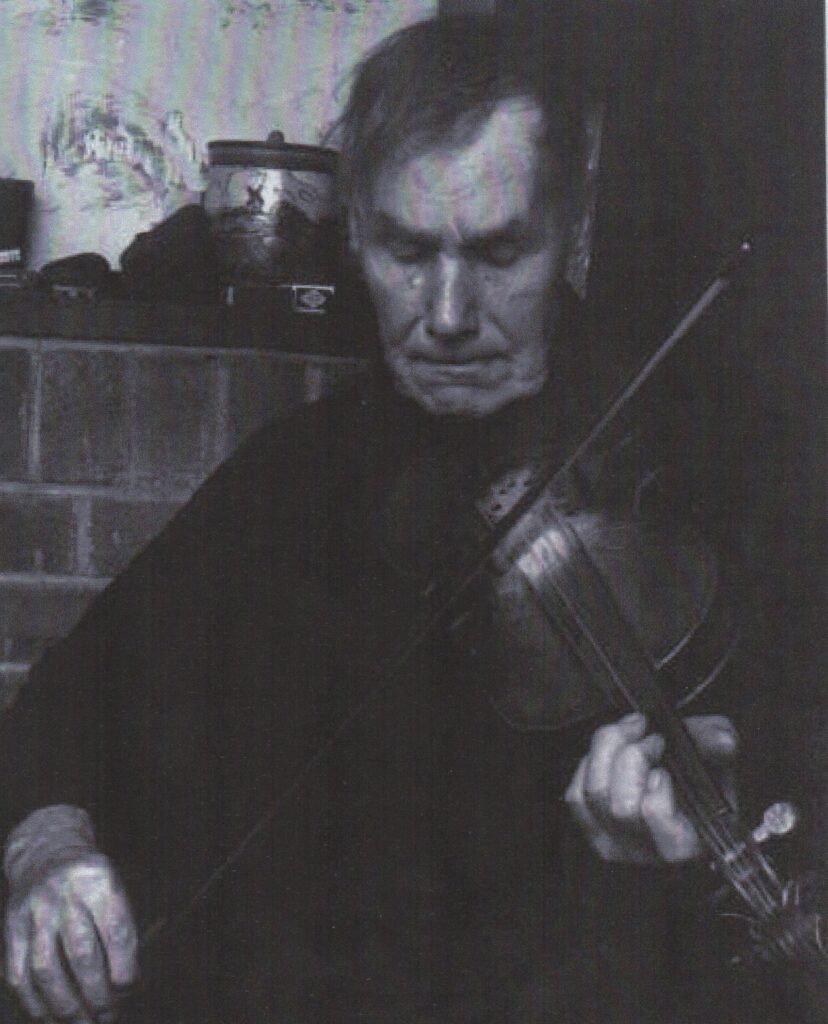

So, Harry was well collected and well remembered, quite rightly. His brother Fred was not.

Moving to Gorleston relatively early in his adult life, Fred was missed by the collectors. According to what little information there is available, he was Harry’s equal in terms of his song repertoire and musicianship. One example is that he taught a great many songs to Caister singer Tom Brown (10).

Reg Reeve, Fred Cox’s grandson, who, of course, knew both brothers well when they were both singing and playing locally (11) recalled: “Harry Cox was my great uncle, although I used to call him Uncle Harry. I was brought up by my grandparents, so as far as I was concerned he was my uncle. My grandfather was Fred Cox, who was Harry Cox’s brother. And they lived like that; houses were there and there. Now, my grandfather, he was a brilliant musician, although he’s dead now of course. I mean, in the house we had a piano, we had an organ, we had a fiddle. He had mouth organs, Jew’s harp, or jaw’s harp; whatever they call it. And a hexagon shape squeezebox (concertina).

“And then I have actually still got his diagonal shaped one, with button keys on the side. That’s a melodeon, isn’t it? I never did know what it was. You play that like a harmonica. That’s a different noise, in and out. (12) This was Fred Cox’s, and nobody actually ever knew about him, to be truthful. He used to sing in the pubs, as they did. He used to sing in Catfield Crown and Sutton Catherine Wheel, and at home basically. But Harry, his brother, Uncle Harry; he was the guy that made fame, didn’t he? But a lot of that old Scottish country dance music (sic) that you were playing, I could remember that through my grandfather. ‘Cause he used to play it on his bits and pieces, and my grandmother (Esther Cox) used to step dance.

“l have to say that’s a shame he weren’t discovered, as well as Harry. Because although Harry was a good old Norfolk singer, my grandfather was more musical. He was more singin’ in tune type person (13). And he’d only have to hear something once, and he’d be away.”

Both Harry and Fred served in the Navy for a while. They both seem to have largely worked on the land however for most of their lives, and could turn their hand to anything. “l spent a winter when I was at school, with Harry, just choppin’ a hedge down. There’s a field between Potter and Catfield; that was a thorn hedge, and I suppose that must’ve been half a mile long, this hedge. We chopped all this hedge down, trimmed it all out, burnt the brush, and he would take all this old thorn wood and cart it all home on his wheelbarrow. And that was all he would use on the fire all winter.”

Fred didn’t step dance either. He acted as musician for the dancing, as did Harry. He had a large repertoire of songs. Reg Reeve remembered a few: “He used to sing, I think it was called Pretty Ploughboy. He always used to crack off on that one. ‘One morning in the month of May, it’s down by the riverside‘.”

In later years traditional music making in pubs was on the wane. Reg Reeve again: “The only music that happened over there was in the little old house at Gorleston. He’d get the old squeezebox out and have a tune now and again. He’d play a penny whistle as good as anybody. Piano, and an organ, but he didn’t have all those instruments when we was at Gorleston. He didn’t have the piano, didn’t have the organ; he didn’t have the piano accordion.”

These two musical brothers from the Norfolk Broads, two of many musicians and singers from the area, did much to continue traditional music making, both in their homes and in various local pubs. As Reg Reeve commented, “Him and Harry; they weren’t inseparable but they used to spend a lot of time together.” Harry of course became renowned as one of Britain’s finest traditional singers, with a certain degree of fame in his lifetime and afterwards. Fred was missed by the collectors, probably because of his move to Gorleston, and sadly there are no recordings of his playing and singing.

Notes:

1 . The Bonny Labouring Boy : Topic TSCD512D

2. Chris Heppa: Harry Cox and his friends: Song Transmission in an East Norfolk Singing Community, c1896-1960 (based on a paper given at the 33rd International Ballad Conference, Austin, Texas); A Life in Song: English Folk Dance and Song Society Journal, October 2001

3. A Visit to Harry Cox: Michael Grosvenor Myer and Bob Thompson; Folk Review, February 1973.

4. See Musical Traditions article 284: Harry Cox: Norfolk Fiddler extraordinaire, by Phil Heath-Coleman.

5. Chris Heppa: A Life in Song, as above (2).

6. Normally called Lord Lovell.

7. Myer and Thompson, as above. (3)

8. Transcript of interview tape with Harry by Michael Grosvenor Myer and Bob Thompson, November 1970. Transcribed by Rita Gallard.

9. See Musical Traditions article 219: E J Moeran; collecting folk songs in East Norfolk – in his own words, by Chris Holderness.

10. See Musical Traditions article 270: Tom Brown, Caister singer- in his own words by Chris Holderness.

11. Interview with Reg Reeve by Chris Holderness and Des Miller, Potter Heigham, 17 February 2006.

12. Many Norfolk musicians referred to their one-row melodeons as ‘out-and-homers’ because of the way they are played.

13. Possible bias here!

Ref CH B11-3