Traditional Fiddle Playing in Norfolk and Suffolk

by Chris Holderness, August 2024

Introduction

That East Anglia has long been an area fertile in traditional music will be familiar to users of this site; something still very evident until very recent times in what Phil Heath-Coleman, writing of the area, referred to as “the last hurrah of traditional music…and its echo.” (1) The area was of course extensively recorded up until recent times and a great many recordings have been issued.

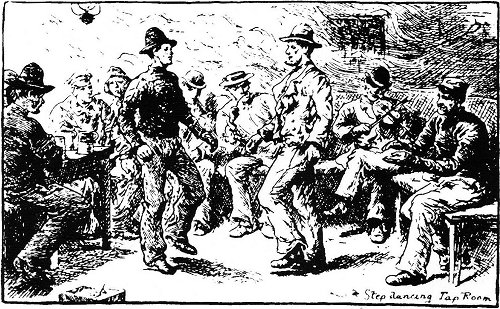

Most recordings featuring instrument playing have perhaps tended to feature the melodeon above all else, discounting the dulcimer tradition – another story in itself. (2) It would seem that accompanying step dancing or, much less frequently, song, was generally the preserve of the melodeon in the first half of the twentieth century or so, with some survivals thereafter.

22 October 1887

The picture emerges of a single musician, perhaps with some form of percussion on occasion, providing the music, generally in their “patch” – on demand in “their” pub or pubs, mostly in a small locality. (3) To a fair extent this seems to have been the pattern across the country. The melodeon was perhaps the perfect choice: relatively cheap (especially the one-row models), fairly robust, easily portable and giving off the required volume, with bass accompaniment, with ease. A harmonica, also popular, had all these attributes in greater measure, of course, aside from volume and bass, and was regularly used for the same purpose.

But what of the fiddle, that old workhorse of country dance accompaniment? Paul Roberts writes that “the popular dance music of pre-Victorian England was dominated by the fiddle and a repertoire of jigs, reels and hornpipes, similar to the one we now associate with Scottish and Irish tradition. This rich musical culture was largely swept away in the middle decades of the nineteenth century by a wave of new music: from brass bands and accordions to imported ballroom dances.” (4) This predominance of the fiddle in the early nineteenth century and before does seem to have been supplanted by the melodeon to a great extent in East Anglia, as elsewhere in England, but there certainly were significant survivals. The extant recordings made of fiddlers in Norfolk and Suffolk in the decades of the 1950s to the 1970s form the basis of this article. Without wishing to get into the debate of what does or does not constitute East Anglia, those two counties are solely represented purely on the basis that there were no recordings made in the neighbouring counties, although there is anecdotal evidence of fiddlers in Essex and Cambridgeshire, and it would be very surprising if it were otherwise. Furthermore, John Howson included a photograph of Mendlesham, Suffolk, fiddler Mr Clements, who was renowned particularly for his hornpipe playing, in his 1985 survey of central Suffolk, Many a Good Horseman, but otherwise pictorial evidence of older generation fiddlers cross the area, reaching back into the nineteenth century, is sadly lacking too.

One question to be considered is if these recorded examples were survivals from an older tradition – as Paul Roberts mentioned above – or merely contemporaneous with what might have “supplanted” it. Another issue is the extent to which the fiddlers played mainly as part of a group – a string band, perhaps, or something similar – or mostly as solo performers, in much the same manner as the pub melodeon player. The great majority of field recordings made in the latter half of the last century are of solo performances, but there is some evidence that some of the local fiddlers did play as part of bands, or ensembles of some description, at times – and in several cases mainly so.

Recordings of English traditional fiddlers are unfortunately somewhat thin on the ground, particularly compared with the richness of Scotland and Ireland, as well as various areas of the United States and Canada. In fact only two full-length albums of English fiddle players have ever been released: of Hereford’s Stephen Baldwin and Suffolk’s Fred Whiting. (5) Fiddlers do appear on many other recordings, of course, and to the above list could be added the English Country Music release in its various forms, featuring Norfolk’s Walter Bulwer (6), although the recording isn’t devoted to him entirely. Peter Kennedy’s collecting trips in the 1950s did yield a fair amount of recordings, mainly from Devon, Yorkshire and Northumberland (7), as well as Herbert Smith of Blakeney in Norfolk. (8) Unfortunately, as with all of these Kennedy recordings, the Herbert Smith material had only limited, semi-commercial release (9) and at the time of writing is not available.

Enthusiasts, particularly Keith Summers, added more from Suffolk – mainly Fred Whiting, Eely Whent and Harkie Nesling. (10) In addition, Norfolk singer Harry Cox was extensively recorded playing the fiddle, as well as melodeon and whistle, by various people, although few tracks have seen the light of day commercially. (11) From these recordings and oral evidence about the musical activities of these fiddlers, and others who were not recorded, it is possible to build up a picture of the extent and nature of fiddle playing in the two East Anglian counties of Norfolk and Suffolk, from men who were born between the early 1880s and 1905.

Writing in the booklet notes to the CD reissue of English Country Music (12), Reg Hall commented, “We should all know by now what a fiddler is: Harry Cox was a fiddler, and so was Scan Tester. Theirs was the traditional music, the aural tradition of the country, characterised not only by their repertory of dance tunes and song airs, but by their technique.” Categorising loosely, it would seem that from the evidence of the six local fiddlers who were recorded reasonably extensively, as well as anecdotal information about them and others not recorded, that the fiddle players fall into three categories. At one end are the “sophisticated” players, the improvisers, who performed to a great extent in a dance band context, as personified by Walter Bulwer and Eely Whent. At the other end were the more archaic players – which doesn’t mean to say that they had no sophistication of their own – who were mainly solo players, such as Harry Cox, Harry Baxter and the sadly unrecorded Alfred Brown. In the middle were players who straddled both categories, such as Fred Whiting, who Reg Hall gave as an example of those “whose music was more urban in origin and, although faked by ear to suit the occasion, at least owed some allegiance to literacy and violin technique”, (13) Herbert Smith and Harkie Nesling, as well as the unrecorded Walter Baldwin. Walter Bulwer and Fred Whiting were certainly musically literate, the former delighting in playing from a collection of sheet music and the latter an avid collector of tune books. There has long been a debate about musical literacy and traditional musician credentials, the hard-liners taking the view that any degree of musical literacy would preclude someone from being considered “traditional”. It’s a debate that I don’t wish to enter into here; suffice to say that there is much more acceptance now that songs and tunes were habitually transmitted in print to a great extent. Certainly musical literacy was (is) commonplace amongst Scottish fiddlers and their Scots-influenced counterparts across the Atlantic, in Nova Scotia; also, many highly-regarded Irish players were openly not averse to dipping into O’Neill (14) from time to time too. On that basis, certainly Bulwer and Whiting should not be precluded from being considered traditional performers, in a wide sense of the meaning, but this does very strongly highlight the differences between these fiddlers, their styles and methods, and that they certainly can’t be lumped together as some sort of “East Anglian fiddlers” group, with largely the same approach and repertoire.

Somewhat echoing Paul Roberts, Keith Summers commented that “up until the middle of the nineteenth century, the fiddle and other related stringed instruments dominated English music and the musician was a vital member of rural society, with a full diary.” (15) He continues that this comprised all events, including those of the church, but that later the church used the piano and organ as “more respectable” (a situation well documented by Thomas Hardy, himself a fiddler and from a family of stringed-instrument players). Keith Summers does add that “both Walter Bulwer and Harkie Nesling…played in church bands as late as the Thirties.” The same was true of Eely Whent. This would suggest that there was some survival of an older tradition, outside the secular dance music, despite the proliferation of the melodeon and concertina from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. As regards secular dance music, both Walter Bulwer and Eely Whent led local bands, performing dance music of varying vintage, at least up to the outbreak of the Second World War, as will be discussed later.

Another apposite point made by Keith Summers is that England had no equivalent of a ‘ceilidh’, the house-visiting once so common in rural Irish and Scottish communities, and therefore English music was functional: “England on the other hand has reserved its music for the pub, harvest supper, country fair and wedding. It has never been a listening music.” (16) Did the fiddle come to be seen as less suitable for a noisy bar than the alternatives? Certainly Harry Cox seems to have thought so: he played melodeon regularly in the pub as a young man, but considered the fiddle too delicate for the job, despite the fact that his father Bob certainly played the fiddle regularly in his local. Is there in fact a generational difference here, which in itself might indicate an older way of doing things being supplanted by a newer one?

What follows is a look at the musical careers of the Norfolk and Suffolk fiddlers who were recorded, as well as a consideration of the bands, for dance or otherwise, which contained fiddlers in the area, for which evidence has come to light. Aside from my own research into the fiddlers in Norfolk, I have drawn upon material from Phil Heath-Coleman, particularly with regards to Harry Cox and Fred Whiting, and Keith Summers, from his collecting in Suffolk, as well as Reg Hall’s booklet notes concerning Walter Bulwer.

Playing in Bands

Six fiddlers from Norfolk and Suffolk were recorded fairly extensively between the 1950s and the 1970s. That is to say, more than just a couple of tracks. With the exception of Walter Bulwer, who was recorded playing with his piano-playing wife Daisy and with dulcimer player Billy Cooper, as well as in an ad-hoc band context during the recordings that were used for the English Country Music album, all the others were recorded solo, aside from Fred Whiting occasionally accompanying dancing – either people or dolls.

The others were Herbert Smith and Harry Cox from Norfolk and Harkie Nesling and Eely Whent from Suffolk. In addition, there is one tantalising recording of Harry Baxter playing Yarmouth Hornpipe for Dick Hewitt to step dance to, in Southrepps, Norfolk, from a BBC broadcast of As I Roved Out from 2 January, 1955 (17) and a couple of tracks of Arthur “Spanker” Austin of Woodbridge, Suffolk, of which only one – a snippet really – has been released. These are solo recordings of these men in their later years and do give an excellent idea of their repertoires. Fred Whiting in particular was very extensively recorded. Conversations with these men, and others who knew them, do make it clear though that most of them did play with others in some form of band, at various times in their musical careers, and it is with this in mind that their activity is considered. A good starting point is with two postcards of Norfolk bands, both dating from before the First World War.

The Hingham Minstrels

This image is of the Hingham Minstrels band, early in the twentieth century, standing outside the Royal Oak pub in the village. Here we have a full ”string band”, blacked-up in the American minstrel tradition. The band members, from left to right, are Charlie Seaman, with mandolin; Walter Baldwin with fiddle; Billy Cooper holding the autoharp and behind the dulcimer; Jack Bunn holding the dulcimer beaters and Bob Felton with the bones. (There is also probably a very youthful Billy Bennington in the background!). It is impossible to know what the band’s repertoire was: to what extent it was as American-influenced as their blackface appearance. The custom of ‘blacking up’ has its English antecedents, of course, if mainly for ceremonial purposes. Unfortunately we don’t know the occasion when the photograph was taken. Certainly American tunes such as Whistling Rufus and Redwing were well known to many English traditional musicians and both were recorded by Billy Cooper with Walter Bulwer (not Baldwin). The former also had Chicken Reel as a dulcimer show piece. From anecdotal evidence, it is likely that they played a variety of popular songs of the day, together with a fair amount of dance tunes. Billy Cooper acquired the nickname the “hornpipe king”, but there’s no direct evidence for him playing for step dancing (18). To what extent musicians learned some of their repertoire from 78rpm records, from across the Atlantic or otherwise, is difficult to ascertain. It certainly seems to have been the case with some, as exemplified by Walter Pardon learning melodeon tunes from his record collection,(19) as did Percy Brown. (20)

Certainly the Hingham Minstrels were not just a one-off band, together for the occasion when the photograph was taken. Several Hingham residents remembered them – as the Minstrels – playing for dances before and during the Second World War. They seem to have retained the name Hingham Minstrels but presumably were not black-faced for their appearances. Walter Baldwin (1888-1949) was one of Hingham’s blacksmiths -not the only instance in this article of a fiddling smith. A second fiddler, Ernie Barber, seems to have been a mainstay of the band later too, particularly after Walter Baldwin’s relatively early death in 1949. Billy Cooper (1883-1964) normally played the dulcimer; Jack Bunn (1886-1964) did so too on occasion, but mainly played guitar later on. So far, information about Charlie Seaman and Bob Felton has proven to be elusive.

As well as playing in Hingham and the surrounding area, the band – or rather a smaller version of it – did range further afield, particularly to Wells-next-the-Sea, on a regular basis. This seems to have been a trio consisting of Walter Baldwin, Billy Cooper and Jack Bunn, with Ernie Barber instead of Walter Baldwin later on. There are two photographs of Billy Cooper and Jack Bunn in Wells and the trips seem to have been quite frequent occurrences. (21) In addition, dulcimer player Billy Bennington (22) recalled many tales, as being part of a trio consisting of Walter Baldwin, Billy Cooper and himself, travelling around the county in Baldwin’s motorcycle and sidecar.

So here we have a busy band, a string band containing two fiddlers for much of the time, active in their area but also outside it, for a great many years. They seem to have played for dances, for other social events and also – in smaller units perhaps – in a great many pubs. This suggests that their repertoire must have been extensive and varied – more than just as a dance band or just as a bunch of pub musicians playing largely popular songs. Walter Baldwin was highly regarded as a player, who could have turned professional as a young man (in what capacity isn’t clear), but decided not to. I haven’t been able to unearth anything about Ernie Barber. Certainly Billy Cooper was an active musician for the whole of his adult life and Ernie Bunn his regular musical companion. The Hingham Minstrels were an active band, containing dedicated musicians and a fairly stable line-up, for much of the first half of the twentieth century.

Blakeney Village Band

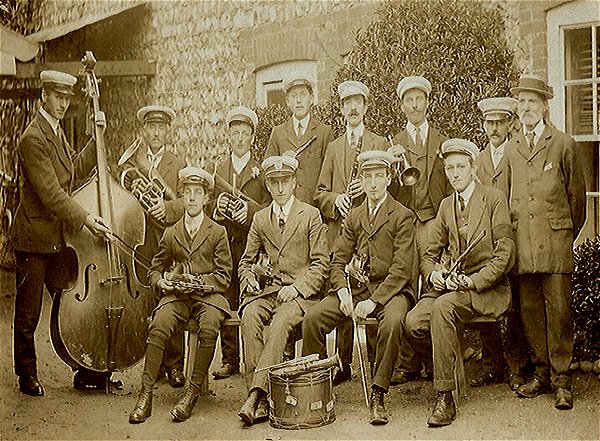

The second postcard features a band of a very different stamp: the Blakeney Village Band. This too seems to date from the very early twentieth century, certainly before the First World War. The location is unknown, but the building in the background seems to be of carstone, which would place its location more likely around the King’s Lynn or Hunstanton areas, rather than Blakeney itself; not very far geographically though. Only three members have been identified: the fiddle player seated on the right is Herbert Smith, another fiddling blacksmith – about whom more later. The bearded man standing at the right is Emmerson Shorting and the tall man, third from the left at the back, discounting the bass player standing to one side, is Herbert Pye. Herbert Smith is wearing a black mourning armband, but nobody else seems to be doing so, so it doesn’t suggest that it’s a time of national events and mourning, such as a change of monarch.

The twelve piece band includes four fiddlers – or would they have considered themselves violinists? The rest of the band is brass and woodwind, as well as – unusually – a three-string bass. An unusual mix perhaps, but maybe not so uncommon. Shipdham’s Walter Bulwer played in a village band as a young man which comprised two violins, viola, cello, cornet, flute and bass fiddle. (23) This band played arrangements of popular songs of the day and I rather suspect that the Blakeney Village Band did the same. Rounding off the Blakeney band’s instrumentation is the drum in the foreground.

This does not seem like a dance band in any usual or traditional sense. Rather, it would seem an outfit to play incidental or listening music to accompany local functions – probably popular songs again – as many brass bands do today. Herbert Smith did play for dances and knew many tunes for them. His musical mentor was Emmerson Shorting, who was most likely the leader of the band. He was a prominent figure in the village and a churchwarden. A portrait of him hangs in the village church today. Did the band perhaps also provide music for church events too? Unfortunately we don’t know anything about the band’s repertoire or where, when and how frequently they played. What may be inferred though is that some musicians, such as fiddler Herbert Smith, seem to have played several musical roles in their communities, as was required of them.

So, two very different bands from Norfolk, from about the same era. Both included fiddle players who were highly regarded in their communities and who seem to have been versatile in their musical activities. Unfortunately we don’t have an image of another band very active in its area of Norfolk, Walter and Daisy Bulwer’s Time and Rhythm band, although it was well remembered by people in the area. With that in mind, it is essential to consider the fiddlers themselves, whether in bands regularly or not.

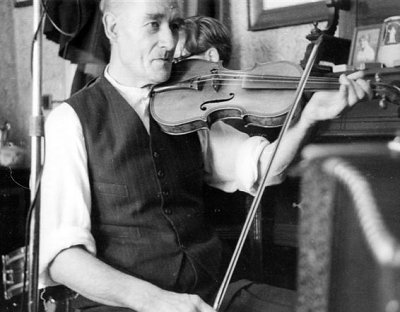

Walter Bulwer

Shipdham fiddler Walter Bulwer was born in 1888. He was an active musician throughout his life, from an early age, particularly leading the Time and Rhythm dance

band. Details about his life, that of his piano-playing wife Daisy, his music playing in the Shipdham area, as well as about Lily Codling – the last surviving member of the Time and Rhythm band – can be found in my Musical Traditions article Walter and Daisy. Bulwer: recollections of the Shipdham musicians by members of their community. (24) He was musically literate but preferred to play by ear. Reg Hall notes that he could play various instruments: violin, piccolo, clarinet, trombone, mandolin and drums (25) and that he was involved in a variety of musical activities in his younger days. He seems to have learned from his father, as did his older brother Chamberlain. Clearly Walter was much more than a rough country fiddler, as Reg Hall writes: “Walter Bulwer seems to have had a foot in both camps, shifting his position according to context between being a country fiddler and a vernacular violinist.” (26)

Walter seems to have initially played mandolin and drums at different times in the Time and Rhythm band, but by 1939 he was the undoubted leader, on fiddle, a position he kept until about 1953. In its later days the band seems to have comprised Reggie Rix (fiddle and mandolin), Horace Everett (fiddle and cornet), Mr Clements (drums) and a teenage Lily Codling (piano accordion) as well as the Bulwers. They played regularly in Shipdham and the surrounding area. Lily Codling recalled many polkas and schottisches being played, as well as tunes for more recent dances such as the samba. She also remembers that Walter Bulwer would paste together the music for medleys of tunes for Daisy, as she preferred to play from the music.

Walter Bulwer was recorded quite extensively in the late 1950s and early 1960s. One set of recordings were made by Sam Steele (27) at some time between 1959 and 1962. There are three tracks where Walter and Daisy play with Billy Cooper (dulcimer) and Edna Wortley (banjo): a medley of hornpipes and the perennial American favourite Whistling Rufus; the third tune – listed as an untitled polka – is Cromartie Polka-March. (28) This last tune was composed by R Heath and published in two versions, one for two banjos and one for banjo and piano, by John Alvey Turner, in Turner’s Banjo Budget in about 1900.The other track on the recording features just Walter and Daisy and is listed as an unidentified jig. It is actually Warbler’s Serenade, a novelty piece first recorded in 1917, of which several versions were issued on 78rpm discs in the forthcoming years. (29) Clearly some of this music was not of any great antiquity. Alan Helsdon has estimated that, of all of the tunes recorded by the Bulwers – or from them – about 80% were published in their lifetimes.

It is much the same with the material recorded by Reg Hall and Mervyn Plunkett between 1959 and 1966, of which the bulk was laid down in 1962. Walter does show himself to be familiar with older, traditional dance tunes, such as when he plays The Irish Washerwoman / The Sprig of Shillelagh as a solo, and with the wonderful tune medley with Daisy, which hinges on The Sailor’s Hornpipe, The Shipdham Hornpipe and The White Cockade, but which demonstrates well Walter’s ability to improvise between the main tunes, more or less creating new tunes as he does so. Of quite a lot of the rest, mostly staunchly traditional fare, it would seem that Walter is seconding and improvising around the tune, led mostly by Reg Hall, who seems to have introduced the tunes into the session. Walter was adept at doing so, and does a great job, even with tunes that he probably was not all that familiar with. The same is true of less traditional material, such as the unreleased medley of American favourites: Polly Wolly Doodle /Marching Through Georgia / Buffalo Girls / Delaware / Camptown Races. Several polkas, either with Walter solo or with Daisy, are from their older repertoire. Lily Codling does remember them as played by the Time and Rhythm band. One, well known amongst more recent musicians as Walter Bulwer’s Polka No 2 demonstrates the diversity of this music, being in the keys of F and B flat (not as generally played today). Another unreleased polka medley included a section from Gilbert and Sullivan, as Walter meandered around the tunes. Reg Hall comments that, when making the selections for the original release of the English Country Music album, there was debate as to whether or not to include such material, of Edwardian origin, as being too far removed for the tastes of the time – although these tunes were quickly taken up and several are now well known and often played, even if not how Walter played them.

The Bulwers had a huge stack of sheet music and apparently spent regular evenings playing through it. This collection has never come to light, unfortunately, after their house was cleared, even though much ephemera has survived. Walter Bulwer undoubtedly knew many traditional dance tunes, many of which – particularly hornpipes – are of some antiquity. He was recorded playing quite a few. However, his

working repertoire was seemingly largely much newer, and comprised a large amount of tunes published in his lifetime. He was an experienced player for dances and dance-band leader for decades. He also played in other capacities earlier in his life.There is no actual recollection of him playing in Shipdham’s pubs, apart from a comment he himself made to Reg Hall about having done so, sometimes in conjunction with another Shipdham fiddler, Alfred Brown. He was in one sense a country fiddler, but certainly much more than that. He is perhaps best described, by Reg Hall’s phrase, as a “vernacular violinist” who could turn his hand to anything musically.

Eely Whent

Another fiddler of a similar stamp was Fred “Eely” Whent (1900-76) from the area around Woodbridge, Suffolk, of whom Keith Summers writes: “The most remarkable fiddle player I’ve ever heard, he really was. He’d played in dance bands. He was a bit like Walter Bulwer, he could do all of that. He knew where all the notes were.” (30) Eely was a self-taught fiddler who had some rudimentary musical training in his youth. He was widely known as an improviser and was adept on several instruments. He played in a fife and drum band after joining the army in 1917, although in what capacity isn’t known. He was also offered the chance to become professional as a young man, but seems to have been dissuaded from doing so by his step father.

Obviously an accomplished and versatile musician, there is little information about the extent of his playing, other than that he performed regularly and for many years in a small band comprising himself, fiddler Arthur “Spanker” Austin and melodeon player Reuben Kerridge. This sounds like a country dance band in a fairly traditional sense, but

unfortunately its repertoire isn’t known. Certainly Spanker Austin fits the profile of the rough country fiddler, living in a caravan in Woodbridge when Keith Summers met him and with quite a reputation as something of a hard-living character. Of the small amount of material recorded from him, only a snippet of the song, Mary Anne, unusual in East Anglia, has been released, although an idiosyncratic version of Soldier’s Joy resides in the Keith Summers collection at the British Library. Aside from in pubs, his band is reported as playing for servants’ balls and in church, suggesting a certain versatility. Certainly Eely Whent was a versatile musician, sometimes also playing banjo and mouth organ (together) alongside fiddler Walter Clow (yet another fiddling blacksmith!).

Eely Whent recalled going to Blaxhall Ship on many occasions with Spanker Austin and that they hung around with traveller brothers Fred and “Lightning Jack” Smith, playing to accompany their step dancing.

Keith Summers recorded quite a few tunes from Eely Whent in 1975. (31) There’s a medley of hornpipes and a country waltz, a sprightly two-step and a polka medley. In many ways fairly standard fare for a country fiddler, although the untitled two-step tune is unusual and seems to be unique to Eely Whent, as far as recordings go. He was also recorded playing the American standard Turkey in the Straw, which he seems to have got from a serviceman stationed nearby. As well as that, we have Red Sails in the Sunset, the popular song written by Jimmy Kennedy in 1935. Clearly his repertoire was a mixture of the old and the newer, as far as we can tell from this small sample. The other track is a medley of unidentified tunes, played on the mandolin – a pair of marches which bowl along nicely after a hesitant start – showing another facet of Eely Whent’s musicality; a comparison can be made here with Walter Bulwer again, as the latter was recorded playing Old Mrs Cuddledee on the mandolin-banjo as well as the fiddle material. (32)

So here with Eely Whent we have a highly-regarded and versatile musician, a man remembered as an improviser and who could play several instruments other than the fiddle. He played regularly with others, as a duo or part of a small band, and seems to have done so for decades. His playing had drive and a sophistication not usually found in a country fiddler; he was, in Keith Summers’ words, “a remarkably creative fiddle player.”

Herbert Smith

Herbert Smith (1892-61) has been mentioned in connection with Blakeney Village Band, above. He was a highly regarded musician in and around his native Blakeney, Norfolk, where he was a blacksmith. Full details of his life can be found in my article Fiddling Blacksmith of Blakeney, published by Musical Traditions magazine. (33) As was common, he seems to have learned his craft from an older man, Emmerson Shorting, also previously mentioned. There is no evidence of his playing instruments other than the fiddle, but he does seem to have been a good singer. He played regularly with Emmerson Shorting for dances in the village, in the early twentieth century, sometimes with a melodeon player too.

Herbert Smith was recorded by Peter Kennedy for the BBC in 1952. Of the dances, he mentioned: “And they’d have a dinner and refreshments, and all that kind of thing. Then they would start off with the good old country dance, like Haste to the Wedding or Pop Go the Weasel, or Tommy, Make Room For Your Uncle; you could play either them three tunes and they’d; most of the company, they thought they had a little whim which tune they; some preferred one and some the other. And sometimes they have about seventy couple up, and you’d have to play them round. By the time you got; played them round; that take twenty minutes. They’d be a good bit exhausted; they’d want a bit of a rest, so they’d have a; fit in a song in between.” (34)

Exhausting work, for both dancer and fiddler, as was the Four Hand Reel, also described by Herbert Smith: “The Four Hand Reel consisted of four of them and they would compete against each other, make from corner to corner; and they would reverse over from one corner to the other, and they’d go round and make a reel of it, you see. They would go round; after the corners they would go round and get into the corners and step again. Why they call it the reel – well, they reel off, d’you see?”

Herbert Smith’s recorded repertoire, unfortunately not very extensive, comprises tunes which, on face value, would be standard fare for the country fiddler and player for dances: several jigs, a couple of polkas, hornpipes, a schottische and a waltz. However, in most cases the tunes are unusual in version or not common in East Anglia. There are three jigs, the aforementioned Tommy, Make Room For Your Uncle and also Starry Night For a Ramble and an unnamed tune for the Long Dance. The first two were fairly common in the area (35) but the third seems unique to the locality. Peter Kennedy gave it the name Rig-a-Jig-Jig, after an American children’s song, with which there is no obvious connection, but it wasn’t called this by either Herbert Smith or Ann Mary Bullimore, landlady of Morston Anchor, who also played it for Kennedy on the pub piano. (36) To them it was just the Long Dance tune. Blakeney and Morston are adjacent villages.The tune seems to be unique to this area: to my knowledge it hasn’t been collected elsewhere. Herbert Smith’s tune for the Four Hand Reel is also unusual, both with its three-part form and with the second and third parts of the tune. Only the first part is “usual” for the tune, in its various versions. Likewise, Blakeney Hornpipe – it is not known whether Herbert Smith actually called it this – is a version of Lass on the Strand, not uncommon as it goes, and with several different names – but this is the only version collected in East Anglia as an entire tune (as opposed to a snippet included in a medley – by Cromer melodeon player Bob Davies). (37)

The old favourites Heel and Toe Polka and Oh Joe, the Boat Is Going Over were also recorded from Herbert Smith, common enough in East Anglia and elsewhere, but the latter was preceded by an untitled tune with three parts, not identified, but which now has gained some currency as Herbert Smith’s Polka. He also played a lovely variant of the tune for the Varsovienna dance, which seems to have been a staple at the local dances. Finally there is the Highland Schottische, common enough as a title, but this version, small snippet of a tune as it is, bears no relation to anything else, as far as I can ascertain. So, in all, a country fiddle repertoire but an unusual one for the area.

Herbert Smith played a highly rhythmic, relatively unadorned fiddle style, ideally suited to the dances that seem to have been his main musical functions. He was perhaps the archetype of the country fiddler in one respect, and yet we have evidence that he was part of a village band set-up in his younger years, which suggests wider musical activity and acumen. Without more evidence of his musical activity across the years, it is impossible to draw further conclusions. It’s a great shame that his solid, austere playing wasn’t recorded to a greater extent.

Fred Whiting

Fred “Pip” Whiting (born in Kenton, Suffolk, in 1905) was certainly a fiddler who was recorded very extensively, particularly by Keith Summers in the 1970s. Much material has been issued, initially some tracks on the Earl Soham Slog LP, released by Topic Records in 1978. (38) Later, he was the subject of a lengthy CD, Old-time Hornpipes, Polkas and Jigs, compiled by Phil Heath-Coleman and released by Musical Traditions in 2011 (39) as well as having tracks included on other CD reissues of Keith Summers recordings. (40) Phil Heath-Coleman has written comprehensively in the booklet notes to the abovementioned CD about Fred’s life and music. I don’t propose to go over such ground again, but refer the reader to that excellent research, which also contains detailed notes about all of the tracks – 42 in total – on the disc.

So, a brief summary here. Fred Whiting came from a musical family. He was a good singer with an extensive repertoire, and also performed with dancing dolls and bones (as well as making them). He learnt many tunes in his community, particularly from fellow fiddler, and older man, Harkie Nesling, directly in the manner that Herbert Smith learned from Emmerson Shorting, as previously described. This is the tried and tested method, of course, for a traditional musician to learn their craft. Fred was unusual in that he was left-handed and played a fiddle strung for a right-handed player. As Phil Heath-Coleman points out, Fred referred to himself as a “fiddling freak” in this respect. Here we certainly have a local musician whose musical development and experience was nurtured within his own community – once again the archetype traditional musician.

Fred saw the value of being able to read music, though, and taught himself to do so as a young man, using William Honeyman’s Strathspey, Reel and Hornpipe Tutor. (41) He also later learned tunes from other books such as the O’Neill Collection and Allan’s Irish Fiddler. Another source of tunes seems to have been the gramophone, according to Fred, although we don’t know what he learned from 78 discs. Closer to home, he certainly learned tunes from local musicians, such as gypsy fiddler Billy Harris, of Chelsworth, whose “hornpipe” (actually a schottische) is included on the Musical Traditions CD.

Fred was an experienced pub player in an area where there was a great deal of music making in the early years of the twentieth century; he played a great deal for step dancing and mentioned to Keith Summers that he used to play mouthorgan or fiddle and dance at the same time. Fred was to return to this activity of Suffolk pub playing later in life, but made a big change in the mid 1920s when he emigrated to Australia. He played a great deal whilst there and seems to have learned a lot from Irish musicians, further broadening his repertoire and experience. Once again, the reader is referred to the wealth of material in the aforementioned CD booklet notes.

So, Fred Whiting was a country fiddler from a community where traditional music making was vibrant and valued. He participated in this from his later teenage years onwards. He had old items in his repertoire which Phil Heath-Coleman describes as being played in “the East Anglian vernacular style” – rhythmic and straightforward, although not without some decoration, particularly with triplets – “the stock in trade of the East Anglian fiddler”. (42) He also was musically literate and added greatly to his repertoire from tune books, These did end up being assimilated into his style however. In addition, in Australia, he had further exposure to a wider experience of music making, as a young man, adding yet more to his store.

To conclude, Phil Heath-Coleman considers Fred Whiting “one of the last great English traditional musicians” and laments the fact that “he was sometimes regarded with suspicion because traditional fiddlers are meant to sound rough and shouldn’t be able to read music.” To return to Reg Hall’s assessment, mentioned earlier, that Fred was an example of someone “whose music was more urban in origin and, although faked by ear to suit the occasion, at least owed some allegiance to literacy and violin technique,” although undoubtedly the case to an extent, this is perhaps an unfair assessment if it damages Fred’s chances of being considered a bona fide traditional musician. He was self taught, grew up in a musical community and played with the style and sensibilities of a traditional musician. He was certainly a very good country fiddler but also a musician whose horizons extended much further than his immediate community; to quote Phil Heath-Coleman again, he was one of a select group of “exceptionally musically gifted players” not perhaps fully appreciated as such in England.

Harkie Nesling

Harcourt “Harkie” Nesling was born in Bedfield, Suffolk, in 1890. He was recorded by Keith Summers in 1975 and it is his information given in the notes for the Topic LP The Earl Soham Slog (12TS374) and the CD releases (43) that is used here. As a young man Harkie moved to London for a while and played in a pit orchestra. The fiddle wasn’t the first instrument he took up – concertina, five-string banjo and mandolin preceded it. Back in Suffolk he played in a country dance band with fiddler Walter Gyford and melodeon player Walter Read. They seem to have been on demand for such occasions as weddings, as well as playing in pubs in villages to the north west of Framlingham, including his native Bedfield (where he was also recorded). In this village the band also played outside the post office on pension day, another aspect of their status as community musicians, in a similar way as did their counterparts in areas of the United States, such as the Virginia duo of banjo player Wade Ward and fiddler Charlie Higgins, who played regularly for such events as farm sales in their community.

There are not a great many tracks of Harkie Nesling’s playing, unfortunately, but what there is does show him to be the consummate country fiddler in one respect, but with unusual tunes or versions of them. A sprightly Barn Dance tune doesn’t seem to be obviously related to anything else that’s currently known. He also plays the Sultan’s Polka – with that, original, title given, for what is usually known as the Heel and Toe Polka, to accompany the dance of the same name. There’s also a snippet – the first part of Impudence Schottische and a medley of polkas, part of which clearly resembles Jingle Bells. (44) Finally for the dance music there’s a very unusual three-part version of Rakes of Mallow; only the first part of this resembles what is more usually played for this tune. (45) In addition, he was recorded singing the song Come and Be My Little Teddy Bear to his own fiddle accompaniment. Finally, Fred Whiting was recorded playing Harkie Nesling’s Stepdance, a tune more commonly known as the West End Hornpipe. (46), one of many tunes he got from his older friend.

Harkie Nesling was obviously very much a community musician and country fiddler. He got his first fiddle tuition, aged fourteen, from a local man, gypsy Billy Smith. From the available evidence, he seems to have spent a lot of time playing as part of a small band in his locality, but also had some wider experience – and presumably with a very different type of music – as a young man. He, in turn, passed on many tunes to others, in particular Fred Whiting. Although he certainly learned other instruments early on – in fact, before the fiddle – there seems to be no evidence as to whether or not he continued playing them later. Despite his age when recorded, his fiddle playing shows the drive of a player for dances and the verve of someone with a lifetime’s experience. In all, he was a highly regarded musician, with long-standing proficiency, in his locality.

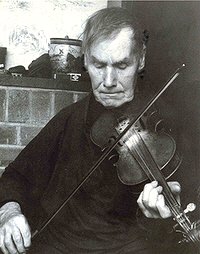

Harry Cox

Harry Cox (1888-1971) is of course one of the most highly regarded traditional singers in the British Isles, if not in a much wider field. His playing of the fiddle and melodeon have been much less celebrated. Although quite widely recorded playing fiddle, melodeon and whistle, little has been issued commercially of the first two instruments, and nothing at all on the whistle. A handful of tracks have seen the light on the commercial releases of his music. (47) He probably is, out of all the fiddlers discussed here, the one that most exemplifies the archetype country fiddler.

Harry learned from his father Bob (1837-1928), who was reputed to be a fine player, and he started playing when he was about eleven years old. Bob Cox played in pubs around the Potter Heigham area of Norfolk, and was able to augment his income to a fair extent by money got by “capping round” – putting the hat round. Harry seems to have accompanied his father to the pub from a young age (48), witnessing his singing and fiddling. Unlike his father, though, Harry doesn’t seem to have played his fiddle in the pub to any great extent. He did however take his melodeon down to local hostelries and is remembered playing for step dancing, particularly to accompany William Miller, an older man who was also a fine singer from whom a few songs were collected. (49) Phil Heath-Coleman has written extensively on Harry Cox’s fiddle style and repertoire in the Musical Traditions article “Ain’t That Beautiful?” Harry Cox: Norfolk Fiddler Extraordinaire (50) and this is essential reading for anyone interested in the fiddle traditions of the area. In this, he concedes that Harry’s playing is “rough, it’s true, and sometimes inexact,” but that it is also “extremely powerful and yet – in its way – precise and sophisticated,” the latter word referring to his accenting of the music. Harry knew a lot of tunes and, as Phil Heath-Coleman points out, they were definitely his tunes and not just performances of standard fare. He seems to have played a great deal alone, at home, for his own amusement and, as Paul Marsh points out (51), he was unusual amongst English traditional musicians in that he played song airs on the instrument.

Harry Cox was extensively recorded playing the fiddle – and melodeon and whistle – as an old man, mostly in the late 1950s and 1960s. Foremost amongst the collectors who did so were Mervyn Plunkett and Frank Purslow, but there were others. Very few of these tracks have been released commercially. Phil Heath-Coleman makes the apposite point that there would probably have been very little interest in them if Harry hadn’t been so widely regarded as a singer. The recordings do reveal a rough player, the performances of an old man who was undoubtedly past his best and perhaps also trying to remember tunes, dredging them up from his memory, for the benefit of those present. Despite this, there is undoubted energy and “attack” in his dealings with a tune, and clear evidence of decades of familiarity with them.

Harry Cox often didn’t know the names of the tunes he played. He seems to have got the majority of them from his father. Of the tunes played on the fiddle, as opposed to the other instruments, the majority seem to be hornpipes. Identifiable ones include Yarmouth Hornpipe, Railway Hornpipe, Bristol Hornpipe, Flowers of Edinburgh, Soldier’s Joy and Kirk’s Hornpipe. He also played song airs like Ladies of Spain and The Fowler. An untitled polka tune was also included on The Bonny Labouring Boy CD set. (52) Harry was sometimes recorded playing the same tune on different instruments and, when this was the case, the versions are very different.

“Harry Cox was a fiddler,” to quote Reg Hall again; he was certainly a country fiddler. We have no way of knowing how he sounded when a younger man but, from the available recordings, he was a rough player – and certainly not musically literate or subject to influences outside his community or usual circumstance – but one who played with the confidence of long experience, which “lends his music a rough majesty,” to quote Phil Heath-Coleman again.

Other players

As mentioned, the half dozen players mentioned above constitute the recorded – or collected – output of fiddlers from Norfolk and Suffolk. Not a huge amount as far as it goes but still the largest amount anywhere in England, with the exception of Northumberland. It is evident from these recordings that there was wide diversity in style. But what of other fiddlers from the area? Most others we know of are mere names. As already mentioned, we have a tantalisingly small amount of recordings of Arthur “Spanker” Austin and Harry Baxter. The former partnered Eely Whent for many years and the latter was the brother of the landlord of Southrepps Vernon Arms, where recordings were made for the BBC. (53) Both of these men seem to fit the profile of country fiddlers, although unfortunately we don’t have much to go on with any appraisal.

“Fiddler Brown”

Another local fiddler of note who was never recorded, but who is worthy of consideration is Alfred “Fiddler” Brown of Shipdham, Norfolk.

Details of Fiddler Brown’s life, as can be ascertained, have been given in my article Alfred Brown: the Life and Times of Shipdham’s Other Fiddler. (54) His sobriquet “Fiddler” seems to have been particularly apt, as it would seem that it was all he ever did.

The musicians mentioned above all worked in various trades for a living. Their status as musicians brought them renown and respect in their communities and undoubtedly, to varying degrees, some financial rewards too. Music was a hobby or a sideline. All held down other jobs. Not so Fiddler. He seems to have done nothing but fiddle for his livelihood, busking in the local towns and pubs, particularly on market days, as in Dereham Royal Standard on Fridays. (55)

He was a wanderer, his wanderings sometimes taking him quite a way from his Shipdham-area base, particularly up to the fenland area around Emneth. He is remembered playing for step dancing; what he played otherwise is impossible to know, although it probably included a large selection of popular song tunes. Where he learned his craft is unknown. Fiddler Brown was fond of his drink – much remembered for being so. He is almost a caricature of the country fiddler; perhaps in a similar vein as Thomas Hardy’s “Mop” in The Fiddler of the Reels. Unfortunately, despite some vivid memories of him, he was never recorded and aspects of his life remain obscure.

The Older Generation: Stephen Poll and George Watson’s Manuscript

If, so far, there is considerable evidence of what local fiddlers played in the first half of the twentieth century or so, what of before that? In the absence of sound recordings, there is little that can shed light on the prevalence and repertoire of fiddle players in the area, but a couple of sources do give us a glimpse.

Sixty-nine year old farm labourer Stephen Poll of Tilney St Lawrence, Norfolk, provided Ralph Vaughan Williams with four dance tunes and a song in 1905. He was born in 1836 and seems to have had long experience as a country dance fiddler in the area, as Vaughan Williams commented:

“He used to learn them at Lynn Fair; when a new dance was danced he used to learn it by dancing it – then later he would ask for the same again and then knew the tune and the dance and could start at the top. He used the fiddle for dances – the old country dances used to have more money in them because each couple as they got to the top would give him a penny.” (56)

On 7th January 1905, Vaughan Williams noted down Trip to the Cottage, Gypsies in the Wood, The Low-Backed Car and Ladies’ Triumph from Poll. The first and last in the list are country dances with wide currency; the other two popular songs. Of those, Gypsies in the Wood was collected as a dance in Cambridgeshire and The Low-Backed Car was written by Irishman Samuel Lover in 1846 – its tune also bears a strong resemblance to the song The Nutting Girl. The song that Stephen Poll sang to the composer was The Foxhunt. He certainly seems to have been a typical country fiddler, playing regularly for local dances, making a concerted effort to learn new tunes and dances and having some financial reward for his role in his community, whilst in no way being a professional musician.

The other source perhaps prompts as many questions as it answers: a manuscript tune bearing the name George Watson, the place Swanton Abbott (Norfolk) and the date. This comprises hand-written notation for seventy-nine tunes, including one duplication. That the tune book turned up by chance in Kent a few decades ago will be familiar to those interested in nineteenth century manuscript books. In many ways this adds to the mystery. What we don’t know is what instrument George Watson played – or even if he was a musician at all.

The George Watson in question was probably born in Skeyton in 1859, worked as a brick maker around the area and died in North Walsham

in 1944. All in the neighbourhood of Swanton Abbott, where presumably he lived when he put his name to the book. Of the seventy nine tunes, the most numerous – twenty-four – are hornpipes. These range from straightforward standards such as Yarmouth Hornpipe, Fisher’s Hornpipe and Harvest Home to more complex, “notey” pieces. Many are unnamed.

The second most numerous are polkas – twenty-two. Most have three parts, most change key and some are decidedly “flowery” in their melodies. There are also thirteen schottisches, with the same characteristics as the polkas – these last two tune types are obviously of much more recent vintage than the hornpipes.

Much less numerous are jigs (four), reels (three) and waltzes (three). The remaining eleven tunes comprise marches, gallops and other assortments. With the exception of the hornpipes, reels and jigs – the tunes of older vintage – the repertoire is mostly nineteenth century in origin, and from quite late in the century at that.

Twelve of the tunes are in the keys of F and/or B flat. This negates the likelihood of Watson (if musician he was) being a melodeon or concertina player. He could well have been a fiddler, but there is really no other evidence to suggest so. So, assuming that George Watson was a musician – fiddler or otherwise – and wrote down the tunes in his manuscript book, here we have someone with a definite, large repertoire of tunes for dances. Tunes of older vintage, such as the hornpipes, rub shoulders with much newer ones, most of which would have been published in George Watson’s lifetime, and some of probable recent vintage in 1890. He was obviously very musically literate – a country fiddler (or player of another instrument), as the repertoire suggests, but one who had the musical training to be able to write this repertoire down.

Aside from George Watson himself, the manuscript book does prompt other questions. Why so many hornpipes? Only a relatively small amount of country dances require a hornpipe-type tune. Some would have suited step dances; others are too complicated and “graceful”. To what extent does the proliferation of polkas and schottisches suggest tunes for well-heeled dances – of the local gentry perhaps? If so, or even if not, did Watson play as part of a band? Was the tunebook his own aide memoire or to enable others to learn his tunes? We shall never know, of course. What is evident, though, is that here is a fairly large repertoire laid out, that some of the tunes are quite complex and there is a wider selection of keys than is usual amongst tunes collected from country fiddlers or other musicians.

The hornpipes in particular are similar indeed to those collected from the recorded musicians above, particularly with tunes from whom quite a few were taken, such as Fred Whiting. Walter Bulwer’s polkas are similar in style and feel to several in the manuscript and Watson’s jigs and standards like Devil Among the Tailors and Soldier’s Joy are universal, but in the manuscript there is a large quantity of relatively new tunes. Perhaps this equates well with the Bulwers’ Time and Rhythm band, with its mixture of the old and the new, even though their activities were separated by decades.

Conclusion

It would seem that it is undeniable that to a great extent the fiddle had been supplanted by the newer melodeon in East Anglia, as the nineteenth century became the twentieth. This seems to have been the case across England as a whole, with the exception of Northumberland. However, the fiddle certainly didn’t disappear in its role as instrument to accompany social dance and enough surviving players were found between the late 1950s and 1970s to provide recorded examples of the last surviving styles and repertoires. It cannot be stated convincingly that the fiddle tradition survived only as the vestiges of an older one; rather, it was contemporaneous with what was happening when the musicians were in their prime and playing regularly. Only Harry Cox really fits the bill as a true country fiddler, learning largely from his father and with a repertoire largely uninfluenced from outside his community and immediate experience. He alone does not seem to have played alongside other musicians and much of his playing – on the fiddle at least – was playing for his own amusement at home.

Several fiddlers played mostly in bands – Walter Baldwin, Eely Whent and Walter Bulwer. Walter Bulwer led his own band for decades and its repertoire mixed tunes for older dances with newer ones. Much of his day-to-day repertoire was not very old. Herbert Smith was a good example of a country fiddler but he too played in the village band, at least as a young man. Harkie Nesling and Fred Whiting had time away from their localities and experienced music-making of different sorts whilst away, Fred Whiting particularly so.

In the bands the fiddle seemed to play a prominent role, as far as we can tell. These fiddlers weren’t really doing anything different from their nineteenth century counterparts. Those who played for dances adapted and expanded their repertoire to suit current tastes, just as George Watson seems to have done. Most of the musicians discussed were involved in the fiddlers’ stock-in-trade of playing for step dancing in pubs and elsewhere. Some, such as Fiddler Brown, seem to have mostly done so, although he seems to have been something of an all-round pub entertainer.

The hornpipes for accompanying the step dancing feature in most of the recorded fiddlers’ repertoires and indeed these do constitute a link with the past, being amongst the oldest tunes – in fact many harking back to the eighteenth century.

So, most of the fiddlers played in pubs regularly. It’s interesting to note, however, that Harry Cox – who sang so frequently in pubs – does not seem to have played the instrument there, even though his father Bob did. It has to be said, however, that as far as pub musicians in the early decades of the twentieth century are concerned, melodeon players seem to have been far more numerous than fiddlers. If the nineteenth century saw a predominance of fiddlers for social dancing and similar activities, times certainly did change. Fiddle players were less numerous in the new century. Those that there were kept the old tunes in their repertoires, as witness the proliferation of hornpipes, but added to them – thus Eely Whent could be recorded playing a medley of hornpipes, but also Red Sails In the Sunset.

Of those recorded, some were close to the archetype rough country fiddler, others were sophisticated and improvisers; some were musically literate, others weren’t. No one style is evident in any way: certainly not some sort of generic East Anglian one. As is to be expected, there is some similarity in repertoire evident, with old favourites such as Yarmouth Hornpipe and Heel and Toe Polka, but also much diversity and a not inconsiderable number of unusual tunes.

The nineteenth century preponderance of the fiddle had certainly disappeared in the next one, but the Devil wasn’t prepared to give up his favoured box completely or lightly. Those practitioners who continued late enough to be recorded later in their lives left behind collectively a rich musical legacy, demonstrating that the repertoires did reach

back into the nineteenth century and before, but which also to a fair extent showed a certain changing with the times and circumstances.

Chris Holderness August 2024

For more articles and Chris’s research into those articles, visit The Chris Holderness Archive on the EATMT website.

References/Notes

- Phil Heath-Coleman: “Ain’t That Beautiful? Harry Cox: Norfolk Fiddler Extraordinaire Musical Traditions article MT284 (2013)

- For further information about the dulcimer in East Anglia, see John and Katie Howson’s research, in particular the website

www.eastangliandulcimers.org.uk and the booklet notes to Veteran CD I Thought I Was The Only One VTDC12CD - A good example of this is Percy Brown being called on to play for the Cromer fishermen in Antingham Barge Inn, whilst they were in the area to collect hazel sticks for their crab pots. See Chris Holderness: Percy Brown: Aylsham Melodeon Player MT211 (2007)

- Paul Roberts: English Fiddling 1650-1850: Reconstructing a Lost Idiom in Play It Like It Is: Fiddle and Dance Studies From Around the North Atlantic (ed. Ian Russell and Mary Ann Alburger; 2006 – Elphinstone Institute, University of Aberdeen)

- Fred Whiting: Old-time hornpipes, polkas and jigs Musical Traditions CD MTCD350 and Stephen Baldwin: English Village Fiddler Leader LP LED 2068 – reissued in a greatly expanded form as “Here’s One You’ll Like, I think” MTCD334 (So I suppose that’s three really!)

- English Country Music. There were three pressings: a very limited edition in 1965, an LP reissue by Topic Records – 12T296 – in 1976, and a greatly expanded CD version, also on Topic in 2000 – TSCD607

- Fred Pidgeon – Fiddle Player of Stockland, Devon Folktrax 087; Yorkshire Country Dances Folktrax 211; North Country Barn Dance Folktrax 121

- Norfolk Village Songs and Dances Folktrax 328

- Topic Records have released some of Peter Kennedy’s recordings as an extension of their Voice Of the People series but, at the time of writing, of the above music, only that of Northumberland has been reissued: “Good humour for the rest of the night” TSCD675

- Keith Summers’ recordings were issued on Topic LP, including The Earl Soham Slog 12TS374 and Sing, Say and Play 12TS375 (both 1978) and later on CD: Good Hearted Fellows VT154CD and A Story to Tell: Keith Summers in Suffolk 1972-79 MTCD339-0. There is little duplication between the releases.

- There are a handful of tracks on the LP English Folk Singer EFDSS LP 1004 and the CDs The Bonny Labouring Boy TSCD512D and What Will Become of England? Rounder 11661-1839-2. In addition, there are examples of Harry Cox’s melodeon playing on The Pigeon on the Gate: Melodeon Players from East Anglia VTDC11CD

- TSCD607, as above.

- TSCD607, as above

- O’Neill’s Music of Ireland – collected and edited by Francis O’Neill and arranged by James O’Neill (1903)

- Keith Summers: English Country Music: A Tradition in Isolation? MT306 (2016)

- Keith Summers, as above

- See Chris Holderness: Southrepps: singing and step dancing in a north Norfolk village MT221 (2009)

- See Chris Holderness: Billy Cooper: the Hingham dulcimer player

remembered by his family MT208 (2007) - See Chris Holderness: Haste to the Wedding: the melodeon playing of Walter Pardon MT253 (2010)

- See Chris Holderness: Percy Brown: Aylsham melodeon player MT211, as above

- See Chris Holderness: Wells-next-the-Sea: traditional music making in a Norfolk coastal town MT196 (2006)

- See the booklet notes to Veteran CD: Billy Bennington: The Barford Angel VT152CD

- From Reg Hall’s notes to Rig-a-Jig-Jig: Dance music of the south of England TSCD659

- See Chris Holderness: Walter and Daisy Bulwer: Recollections of the Shipdham musicians by members of their community MT185 (2006)

- Reg Hall, as 23 above

- Reg Hall, as 23 above

- Released on Veteran CD Heel and Toe VT150CD

- Information provided by Adrian and Sue Carlton

- Identified by Alan Helsdon

- Keith Summers: booklet notes to MTCD339-0, as above

- Tracks have been released on 12TS375, VT154CD and MTCD339-0, as above

- Released on TSCD659, as above

- See: Chris Holderness: Herbert Smith: Fiddling Blacksmith of Blakeney MT179 (2006)

- See: Chris Holderness: Southrepps.., MT221, as above

- For example, Sustead melodeon player George Craske was recorded playing the former – released on VTDC11CD – and the latter was published by EFDSS. Both tunes are somewhat different from Herbert Smith’s versions.

- Folktrax 328, as above

- Released on VTDC11CD, as above

- 12TS374

- MTCD350, as above

- 12TS374, VT154CD and MTCD339-0, as above

- William Honeyman: Strathspey, Reel and Hornpipe Tutor pub. Edinburgh; E Kohler and Son (c1898)

- MTCD350

- VT154CD and MT339-0

- George Craske also played a version of Jingle Bells as a polka tune – released on VTDC11CD, as above

- Keith Summers made the comment that Harkie Nesling’s tune was similar to that used by Yorkshire fiddler Peter Beresford for the Ninepins dance (rec. Peter Kennedy; Folktrax 211, as above). I fail to see the similarity though. Beresford’s version is very much the “usual” one, whereas Nesling’s one most certainly is not.

- For further information about this, and other tunes mentioned, see the EATMT tune book: Before the night was out… (2007)

- EFDSS LP 1004, TSCD512D and Rounder 11661-1839-2

- Paul Marsh, in the notes to TSCD512D, as above

- It was long believed that William Miller’s nickname was “Bullets” but, as Chris Heppa has pointed out, it is more likely to have been “Bullards” – after the brewery, and maybe his favourite beer. He can be heard on East Anglia Sings SFO 005

- MT284 (2013), as above

- Paul Marsh, from TSCD512D, as above

- TSCD512D

- See Chris Holderness: Southrepps…MT221, as above.

- See Chris Holderness: Alfred Brown: the life and times of Shipdham’s other fiddler MT186 (2006)

- See Chris Holderness: Billy Cooper… MT208, as above

- This has been quoted often, but in this instance I have taken it from Phil Heath-Coleman: Boshamengro: English Gypsy Musicians MT310 (2017) –

CD booklet notes

Postscript

Many thanks are due to Phil Heath-Coleman for his previous research and writings, but also for his suggestions in relation to this one. Alongside such suggestions, he had this to say about the fiddlers discussed: “For what it’s worth, to my mind Harry Baxter and Bert Smith have something (sophisticated) in common in their hornpipe playing which I suspect might reflect an older (Victorian? – I hesitate to say traditional) general way of playing them (presumably for stepping). I also have a playlist which has Bert Smith’s and Harry Lee’s* Lass On the Strand in succession, which surprisingly reveals their playing to be nigh identical. Walter Bulwer’s hornpipes are similar, but less ‘immediate’ – perhaps his repertoire was divorced from stepping. Fred Whiting’s ‘sophisticated’ hornpipes, even those from Honeyman and O’Neill, seem to betray familiarity with the same way of playing them.”

*Gypsy fiddler recorded in Kent by Ken Stubbs in 1962. See note 56, above.